"Architecture is the only art form which has a direct, daily impact on the quality of human life"

- His Late Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan IV

Aga Khan Award for Architecture

Ceremony 2016

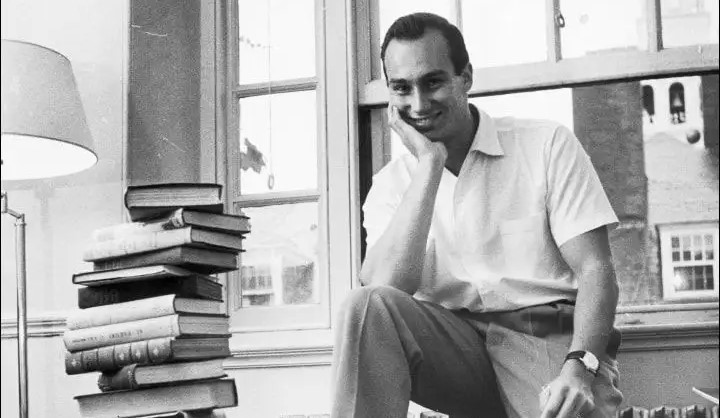

Known as Mawlana Shah Karim to many, His Late Highness Aga Khan IV, the 49th Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims, was a visionary who saw architecture as a vessel of change.�

Architecture of any country is a direct reflection of its ethos. In the years following independence, Pakistan’s architecture was largely shaped by modernist influences—many of which continue to be appreciated to this day. As the Zia era unfolded, however, architecture, like much else, became draped in the rhetoric of Islamization. It was during this moment that Prince Karim Aga Khan emerged with a rare architectural sensitivity, a visionary who understood architecture not merely as structures of stone, but as vessels of history, identity, and human connection.

Table of Contents

ToggleAs reflected by his daughter, His unwavering commitment to architecture was rooted in a profound belief in its ability to remain non-political, even while shaping societies. He envisioned a revival of the poetics of Islamic architecturenot as pastiche, but as a living legacy inherited from his forefathers.

His contribution to Pakistan’s built environment extends far beyond patronage. Through institutions, intellectual frameworks, and carefully chosen architectural interventions, the Aga Khan articulated a vision of architecture that was modern yet rooted, global yet local, progressive yet deeply respectful of tradition. For Pakistan—a nation still negotiating its postcolonial identity—this vision proved quietly transformative.

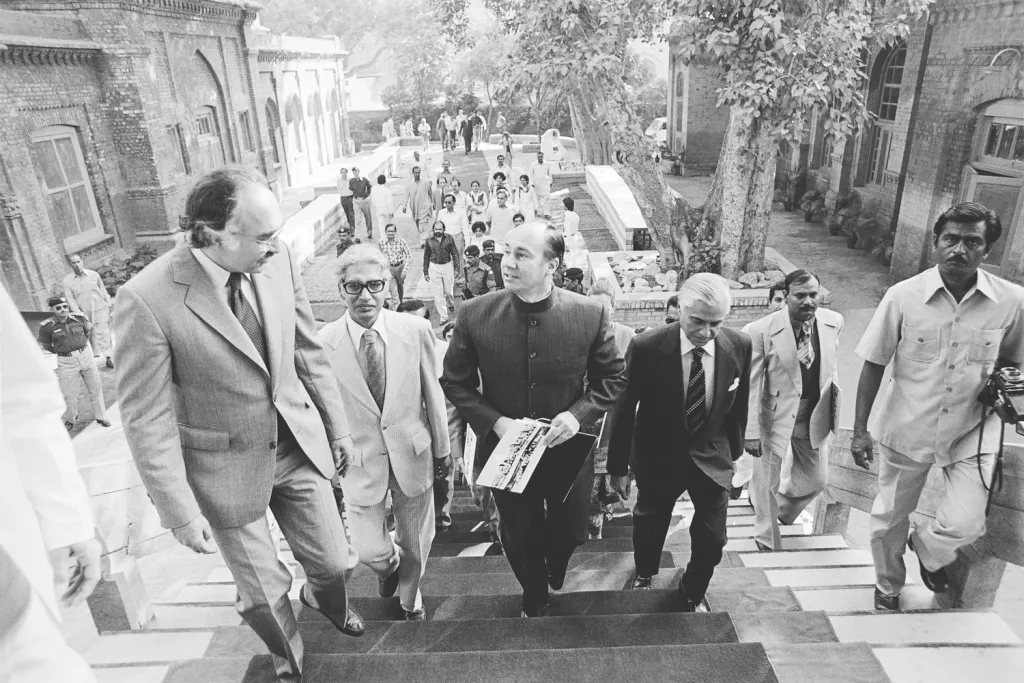

Prince Karim Aga Khan during a site visit

Architecture as Cultural Continuity, Not Nostalgia

His Highness has always viewed architecture as more than just an aesthetic pursuit. For him, it is a tool for social change, – a means restore cultural identity, and an inspiration to building better future. A bridge between different civilizations. He believes that architecture should serve people by addressing their needs—whether economic, social, or environmental. His vision underscores the importance of culturally sensitive design that respects history while embracing innovation.

At the heart of Prince Karim Aga Khan’s architectural philosophy lies a refusal to treat tradition as a static artifact. Instead, he advanced the idea that Islamic and regional architectural traditions are living systems—capable of adaptation, reinterpretation, and innovation.

Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi

“The Award was designed, from the start, not only to honour exceptional achievement, but also to pose fundamental questions. How, for example, could Islamic architecture embrace more fully the values of cultural continuity, while also addressing the needs and aspirations of rapidly changing societies? How could we mirror more responsively the diversity of human experience and the differences in local environments? How could we honour inherited traditions while also engaging with new social perplexities and new technological possibilities?”

His Late Highness Aga Khan IV The Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2013 Ceremony, Lisbon, September 2013

Reviving the Glory & Poetry of Islamic Architecture

One of Aga Khan IV’s most significant contributions has been his commitment to reviving the grandeur of Islamic architecture, particularly from the Fatimid era. Under his leadership, efforts have been made to restore historical sites and encourage contemporary architects to draw inspiration from Islamic heritage without merely imitating the past.

Through the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme (AKHCP), major restoration projects have been undertaken, bringing back the spiritual and artistic essence of Islamic civilizations while making these spaces relevant for contemporary use. His focus has been on the preservation of mosques, madrasas, palaces, gardens, and entire urban neighborhoods, ensuring that their beauty and function continue to serve communities.

One of the defining aspects of his work has been to reintroduce Islamic architectural elements like courtyards, intricate geometric patterns, and sustainable design techniques into modern urban environments.

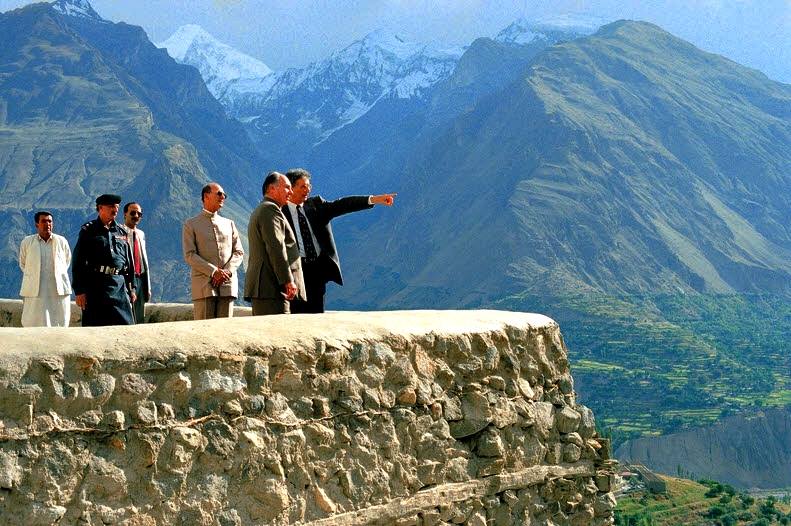

Prince Karim Aga Khan inspects a project of Aga Khan Rural Support Programme in Teru area of Ghizer in 1983

Projects such as the Baltit Fort and Altit Fort restorations in Gilgit-Baltistan exemplify this approach. These were not mere architectural restorations; they were cultural, economic, and social revitalization projects.

From an architect’s perspective, these projects demonstrated that:

- Conservation must engage local communities and craftspeople.

- Traditional construction knowledge is a form of intellectual capital.

- Architecture can be a catalyst for regional identity and economic resilience.

In a country where heritage is often neglected or commodified, this model reshaped how architects, planners, and policymakers understand preservation.

H.H. Prince Karim Aga Khan IV and Prince Amyn Aga Khan taking a view of The Hunza Valley from the vantage point of 800 years old Baltit Fort.

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture: A Global Platform with Local Impact

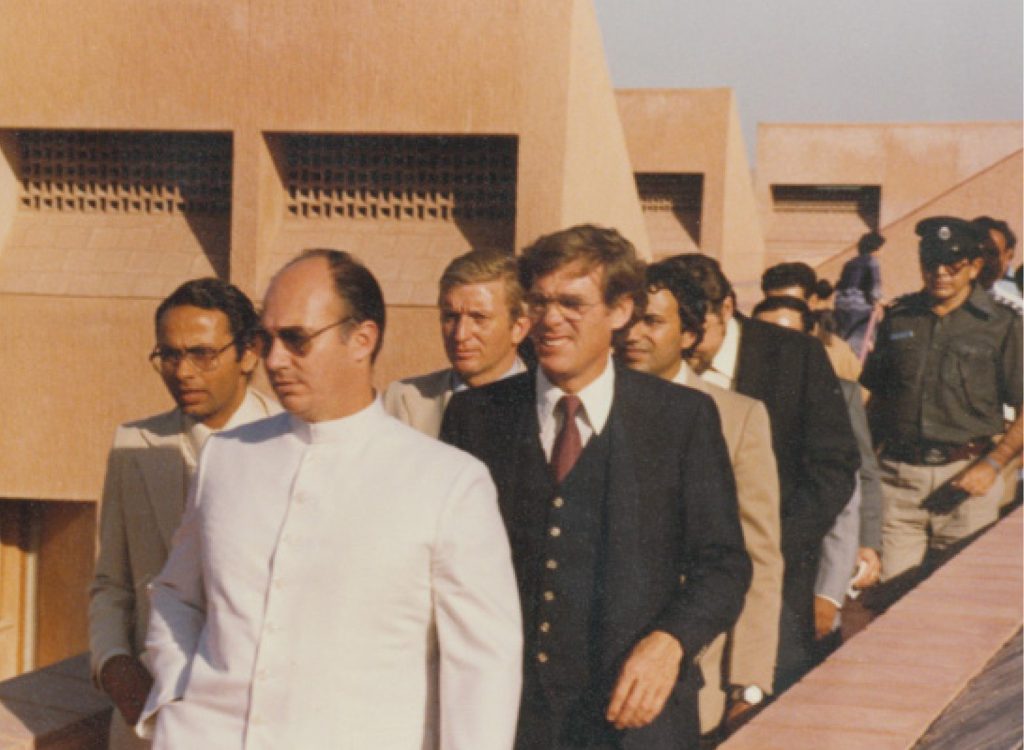

In His speech at the inaugural of Aga Khan Award of Architecture he empathized on “how great architecture can integrate the past and the future – inherited tradition and changing needs. We need not choose between looking back and looking forward; they are not competing choices, but healthy complements”.

Perhaps Prince Karim Aga Khan’s most far-reaching contribution to Pakistan’s architectural discourse has been the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA), established in 1977. First ever ceremony of which was held in Shalimar Garden, Lahore.

For Pakistani architects, the Award did something unprecedented: it validated local architectural practices on an international stage. Projects from Pakistan—ranging from social housing and heritage conservation to contemporary institutional buildings were judged not against Western formal standards, but against criteria of social impact, environmental response, craftsmanship, and cultural meaning.

The Award reframed success. It told architects that:

- Architecture serving marginalized communities mattered.

- Conservation was a creative act, not an academic exercise.

- Regional materials and techniques could be intellectually rigorous and globally relevant.

This shift quietly but powerfully altered architectural education, practice, and ambition within the country.

The Aga Khan’s interventions proposed a third path: one where place, climate, material intelligence, and social use shaped contemporary design.

This philosophy challenged architects to move beyond surface aesthetics arches, domes, and motifs and engage with deeper spatial, environmental, and cultural logics embedded in South Asian and Islamic architecture.

Award of Architecture Ceremony in Lahore, 1980

The Aga Khan University Hospital - A must needed contextual Architecture

Prince Karim Aga Khan’s vision for Aga Khan University Hospital was perhaps not just a hospital but a building that reflects the spirit of Islam. �

Payette’s approach therefore was a process of discovery. It drew upon both his Modernist inheritance and fundamental elements of the Islamic design heritage. Conceived as an integrated ensemble of buildings, verandas, and courtyards, AKUH resists the idea of the hospital as a singular object. Instead, it reveals itself as a sequence of interlocking spaces outdoor rooms that feel almost interior in their sense of enclosure and purpose. Moving through the campus, one experiences a gradual transition from exterior to interior, from public to private, from movement to pause.�

These courtyards are not residual spaces; they are carefully imagined places of use and meaning. Some offer quiet moments of contemplation, while others become shaded waiting areas where families gather, often holding silent vigil for loved ones undergoing treatment.

Taken from Islamic Architecture, the building was Landscaped with restraint through water, texture, and shade these spaces create a humane microclimate that stands in gentle opposition to Karachi’s harsh environment. Long before the language of “healing gardens” became commonplace, AKUH embodied the idea that architecture itself could participate in the act of healing, offering dignity and respite to patients, caregivers, and students alike.

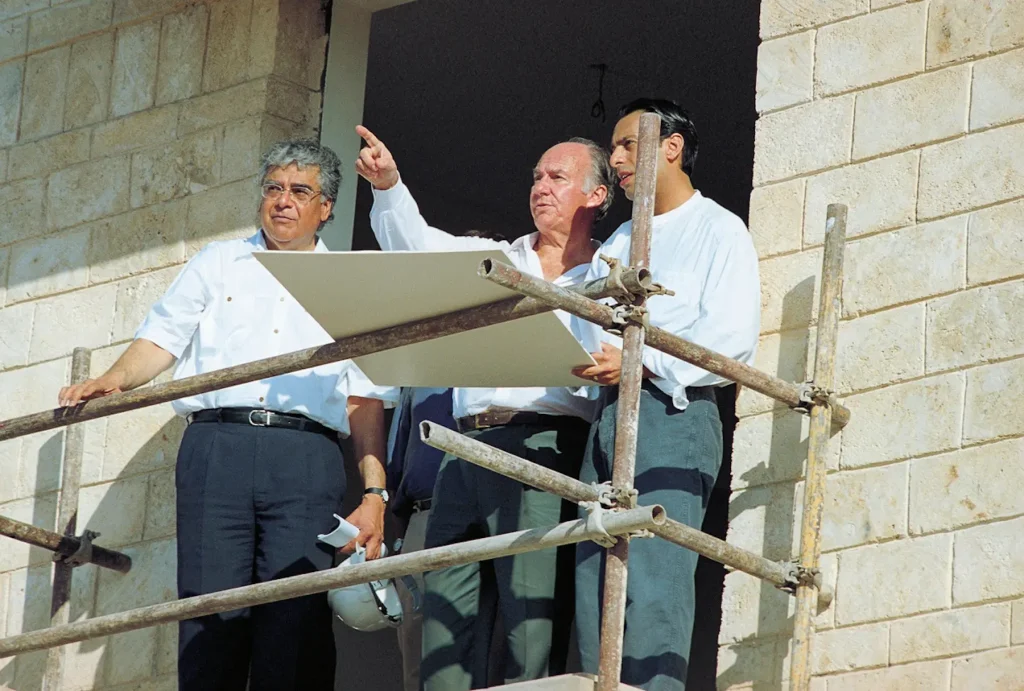

Prince Karim Aga Khan with Tom Payette during the visit of The Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi

Institutional Architecture and the Cultivation of Design Intelligence

Beyond healthcare, the Aga Khan Development Network’s commitment to education reveals a similarly thoughtful architectural ethos. AKDN’s educational institutions in Pakistan are not conceived as isolated buildings, but as carefully structured environments where learning unfolds through space as much as curriculum. Classrooms, courtyards, libraries, and circulation spaces are composed to encourage interaction, reflection, and a sense of belonging qualities often overlooked in conventional educational architecture.

What distinguishes these institutions architecturally is their quiet intelligence. They respond to climate through orientation, shading, and materiality rather than reliance on mechanical systems. They draw from regional building traditions without replicating them, allowing brick, stone, and light to carry both function and meaning. Circulation is never merely transitional; verandas and shaded corridors become informal learning spaces, places where dialogue extends beyond the classroom.

These buildings consistently demonstrate:

- Climatic intelligence over mechanical excess.

- Spatial clarity over formal spectacle.

- Human-scaled environments in large institutions.

In these campuses, Prince Karim Aga Khan’s belief in education as a transformative social force becomes spatially legible. Architecture is not treated as a symbol of authority, but as an enabler of curiosity and dignity. By privileging human scale and contextual sensitivity, AKDN’s educational buildings quietly challenge the notion that excellence must be monumental. Instead, they suggest that enduring architecture—much like meaningful education—is rooted in care, restraint, and an understanding of how people truly inhabit space.

Prince Karim Aga Khan’s influence is also evident in Pakistan’s institutional architecture, particularly educational and healthcare buildings commissioned by the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN).

Professional Development Centre, North (PDCN), Gilgit-Baltistan�

His Highness's Vision for the Developing World

Aga Khan IV’s work has had a profound impact on urban planning and architecture in the developing world, particularly in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. His initiatives focus on human-centered architecture, which prioritizes:

- Affordable housing and sustainable urban development

- Restoration of historic city centers to enhance cultural identity

- Public spaces that promote social interaction and economic activity

- Sustainable architecture that respects environmental concerns

Through AKDN (Aga Khan Development Network) projects, communities in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria, and Mali have benefited from architectural interventions that preserve heritage while improving quality of life.

"Architecture is the only art form which has a direct, daily impact on the quality of human life"

- His Late Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan IV

His Highness the Aga Khan in Lahore, Pakistan.

Ismaili Imammat and Architecture - a means of Change

You may ask as many have asked, then and since. Just why should the Ismaili Imamat become so deeply involved in the world of professional architecture?

The simple answer lies in my conviction that Architecture, more than any other art form – has a profound impact on the quality of human life. As it has often been said, we shape our built environment and then our buildings shape us.

This close relationship of architecture to the quality of human experience has a particularly profound resonance in the developing world. I believe that we all have a responsibility to improve the quality of life whenever and wherever that opportunity arises. Our commitment to influencing the quality of architecture – intellectually and materially, grows directly out of our commitment to improving the quality of human life.

Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2019�

A Legacy of Architectural Excellence - Beyond Form

His Highness Aga Khan IV’s contributions to architecture have left a lasting imprint on both the Islamic world and the West. His work revives historical glory, fosters modern innovation, and bridges cultural divides. Through his philosophy of architecture as a means of social betterment, he has ensured that the built environment serves people while preserving the spiritual and artistic traditions of the past.

Prince Karim Aga Khan’s greatest contribution to Pakistan’s architecture may not be a single building or project, but a shift in values.

He helped move Pakistani architecture:

- From imitation to interpretation

- From object-making to place-making

- From elite symbolism to social relevance

For architects, his legacy is both a gift and a challenge. It asks us to design with humility, intelligence, and responsibility—to see architecture not as a stylistic pursuit, but as a cultural and ethical practice.

In a rapidly urbanizing Pakistan, grappling with climate crisis and social inequality, this vision remains not only relevant, but urgently necessary.

His architectural legacy will continue to inspire generations, proving that architecture is not just about buildings—it is about shaping civilizations, fostering dialogue, and creating a better world for all.

Yesterday I was sitting in architectural discourse masterclass by Ar. Yawar Jillani (my favorite Pakistani architect) organized through Institute of Architect’s Pakistan. He spoke about the profound contributions of His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan to Pakistan’s architectural landscape; and how he not only brought meaningful architecture but a discourse of identity.

Sitting there, immense gratitude filled my heart — I cannot thank Allah enough for not only making me an Ismaili but also an architect!�

Ar. Yawar Jillani, conducting MasterClass at IAP, Karachi – December 2025